Legendary Athlete: Warren Armstrong Jabali

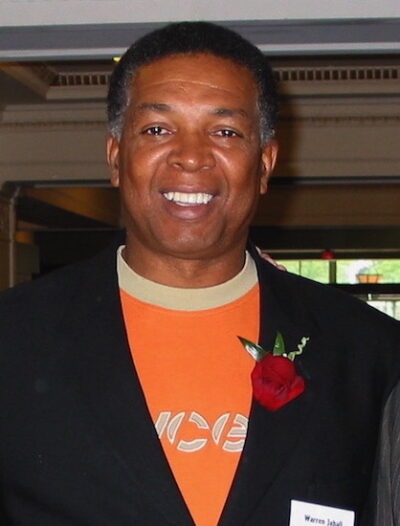

I can’t think of anyone I admire more than Warren Armstrong Jabali. The fact that he opened his life to me and allowed us to became friends was a great gift for which I will always be grateful.

Warren showed me his world. He introduced me to his friends, several of whom are now my friends. We did projects together. I attended his 60th birthday celebration in Miami and within six years of that celebration, sadly, I was among those who eulogized him at his funeral.

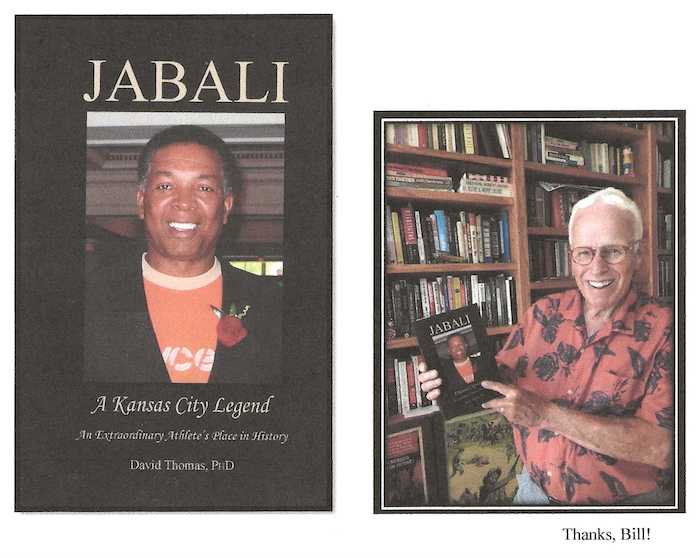

One of the things for which I am most proud is the initiative to have the Interscholastic League Field House Court in Kansas City, Missouri named in Warren’s honor. That story, as well as the story of Warren’s career, is contained in the book I published in 2019, entitled JABALI: A Kansas City Legend.

One of the things that so pleased those of us involved in the court-naming initiative was that Warren was alive and well for the dedication. He and his wife, Mary, flew from Florida for the event. For more on the court-naming initiative including the video I prepared for the luncheon on the day of the court dedication, go to PROJECTS: THE COURT-NAMING INITIATIVE.

What follows is the first essay I wrote about Warren. It was published on the Remember the ABA website and in response I heard from individuals from around the world. Invariably, they wrote to say that they, too, had seldom seen such a player, and in some cases, they wrote to praise him as a person.

For Warren Jabali: A Tribute to a Great Player

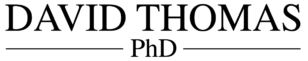

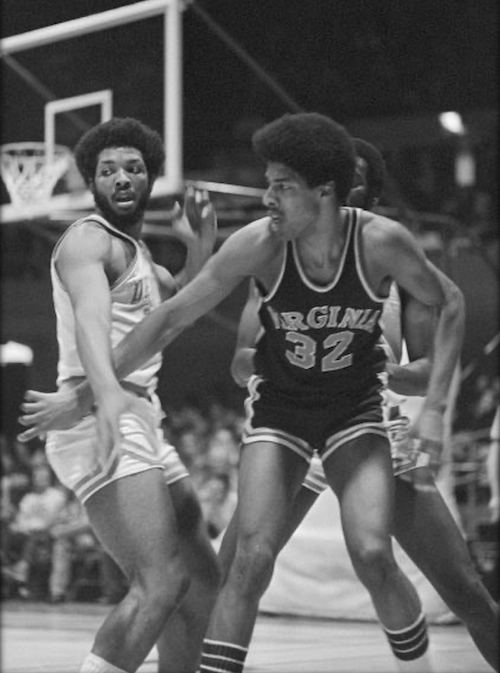

I played against Warren Jabali (formerly Warren Armstrong) in high school. He was the greatest high school basketball player any of us had ever seen. This was Kansas City, Missouri in 1963 and ‘64 and some of the best high school basketball in the country was being played here. Lucius Allen was across the river in Kansas City, Kansas. Jo Jo White came up from St. Louis for the state tournament. Other remarkable players went on to have solid college careers, even pro careers, but the best—and everyone knew it—was Warren Jabali.

Here are excerpts from the Kansas City Star’s coverage of the 1963 Missouri State Basketball Tournament:

Armstrong, opening with a flash of brilliance, turned friend and foe alike goggle-eyed as he rebounded, blocked shots and funneled in 26 points on his own.

Then Armstrong scored on a tip-in, stole the ball and stuffed in a 2-hand dunk shot that almost pulled the basket off the backboard.

Armstrong now has pumped in 87 points in his last three games, and it was his 17 points in the first half that got the Eagles off and flying.

With apologies to the ones I didn’t see, the best all-around players I saw were Warren Armstrong of Kansas City Central in Class L, . . . only a junior, Armstrong faces a great future if he consistently exercises all his tremendous talents.

It’s important to remember that Jabali was only 6’2”. Important also to remember that he could fly, really fly—a fact not known by those who came late to the ABA. I once saw him graze his forehead along the rim. It occurred in that same state tournament following a very slick steal and in the middle of a slam dunk that brought everyone to their feet. It was an electrifying time. Legendary. In Kansas City, to this day, among men of a certain age—Black and white—there is a bond because of it.

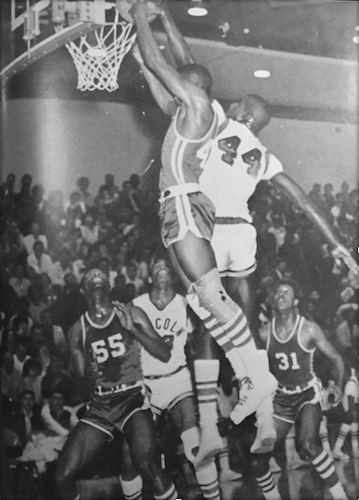

Jabali went on to set rebounding and assist records at Wichita State and was, at the time, their fourth all-time scorer. His senior year, Wichita State was considered to have the most difficult schedule of any college team in the country. Still, it was Wichita State. Had Jabali gone to Kansas or UCLA, he would not have been—or be today—so little known.

Following his senior year, Jabali signed with the Oakland Oaks in the ABA for what was even then a modest amount. The first thing he did with his signing bonus, his mother told me, was to free his father from one of the two jobs he had held for years.

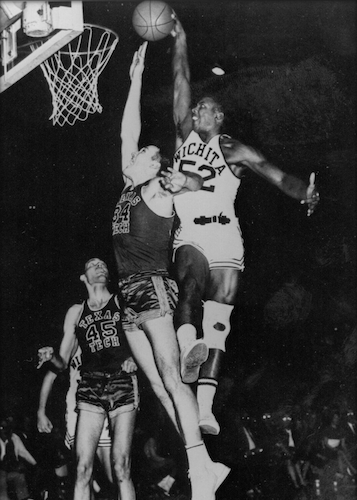

His first season in the ABA, Jabali won Rookie of the Year honors. Here is what Rick Barry, his teammate, said of him:

“He’s unbelievable. As a guard, he’s in a class by himself. I’ve never seen a player his size with so much strength. As great as Oscar Robertson is, well, he couldn’t come close to matching Armstrong in jumping and rebounding. Nobody can. He can out-jump and out-score the Warriors’ Al Attles. He’s stronger than I am; stronger than Robertson. He’s so powerful that even at 6’2”, he can come in and rebound with 6’7” forwards. And you should see him drive into the basket. No doubt he’s one of the best guards I’ve ever played with—or against. Just wait till he gets more experience—nobody will be able to stop him.”

It was an injury to his back and another to his knee that stopped Jabali, or at least slowed, and lowered, his high-wire act. Even so, he exerted a commanding presence. His fifth year in the league he was voted “Most Valuable Player” in the All-Star Game held in Salt Lake City, a game that included Julius Erving, George McGinnis and Artis Gilmore. That same year he was First Team All-ABA Guard and later, Alex Hannum called him “the smartest player I ever coached.”

I lived in Denver when Jabali played for the Rockets and went to nearly every game. It was a great pleasure for me to watch Jabali do what I felt he had always done, control and direct the game. He knew where to stand and what to do. The game flowed from him and through him as he interacted creatively with it (much like Larry Bird later would do) and for that reason alone he remained for me the most fascinating player by far to watch.

Once, in a very close game against my high school team, Jabali made a beautiful 30-foot jump shot, giving his team a lead they held to the end. When he made the shot, I heard my coach disgrace himself by calling Jabali a freak. Jabali was anything but a freak. He was the star of the show. When the Denver Rockets had “Halter-Top Night”—yes, that’s right, Halter-Top Night!, the two winners (“Best Halter-Top Outfit” and “Best Looking Girl in a Halter Top”) were asked to name their favorite Rocket. Both answered, “Warren Jabali.”

And yet, for all of this, there was apparently another side. I do not know the details surrounding the Jim Jarvis incident nor have I ever seen the tape. I did see Jabali’s temper on two occasions, once in high school in response to a series of intentional fouls, and once with the Rockets in response to a hard elbow to the lower back. On both occasions, he stopped short of anything that would have removed him from the game.

He was tough, no question about that, and strong, and proud; and he had a remarkable presence. In high school we sometimes remarked on how everyone in the league—or so it seemed—walked like Warren Armstrong. But even there—despite ourselves—we were on to something; walking—one of the four “dignities of man”. And Jabali did have dignity. He may have lost it on occasion. The Jim Jarvis incident may be something he deeply regrets. I do not know. But for him to be remembered as a thug seems way off to me. I never saw a single incident in his two years as a Rocket that would justify such a label. Indeed, I saw quite the opposite.

Nevertheless, after his most effective year as a pro, his last season with the Rockets, he was released and not a single team picked him up. He was an unemployed All-Star guard. Of course, he also had been the player’s representative and had led the black players boycott of a recent All-Star Game. He did have a reputation as a militant and he no doubt did champion unpopular views. It’s also the case that the Denver franchise was in trouble and even Larry Brown was quoted in one newspaper report as saying that Jabali had been made the scapegoat. I do not know the whole story. I do believe, however, that whatever the story, the truth itself was served by another of Brown’s comments (from the same report): “Warren has . . . never been hesitant about expressing himself,” said Brown. “But he’s a person of high ideals, and an unselfish, dedicated basketball player.”

Nine months after his release from Denver, Jabali was picked up by the San Diego Conquistadors with whom he played out the season, the last season of the ABA. Shortly after his arrival, Alex Groza, the San Diego coach said, “One guy has made a difference in this team. Warren is a very smart basketball player. He never gets excited, keeps his cool and helps out the other guys.” Said back court partner, Bo Lamar: “This is a different team. Warren has made a big difference. . . every team has a leader. But before we got Jabali, I don’t think this team had one. . . I think he inspires the rest of us and gives us confidence.”

This is what Jabali did from very early on. He played with intelligence, often inspiring others with spectacular play. For many of us in the Kansas City area, he represented the first time we had seen such a gift. It was genius, foreshadowing what we later would see in a host of players who now are the new standard. Had it not been for injuries to his back and knee, had it not been for the politics of the time, had it not been for the specific requirements of his own development as a person—whatever they were, many more people would have had the pleasure of watching a truly gifted and remarkable player. As it was, many did see him play and many of these, myself included, were enriched by it.

I believe that if you are given a talent, then you must use it. There may be exceptions to this but on the whole, I believe this is so even though you may never know the good that comes from it. A great talent, like the one Jabali was given, may excite and entertain, it almost always does, but it also does more. Invariably, it leads to reflection and self-review. “What is my gift?” asks the person who is conscious of what he is seeing, “And how can I bring it out?” We were all better off in Kansas City for having witnessed the great early—and then later—years of Jabali’s career; his brilliance made better players of us all though the “games” we chose to play came to vary considerably. I do not know if Jabali ever knew of this, of how his great play, the expression of his remarkable gift, was also a community service, raising and expanding our standards and aspirations. Many of us, I am sure, were never consciously aware of it. But I deeply believe it is so.

In 1975, the Kansas City Star carried an article reviewing Jabali’s career. Jabali had been invited to speak in a newly built community center to the kids playing in the league that carried his name and the article quoted Jabali’s remarks.

“Some of you probably saw the movie Super Fly,” Jabali began, then fixed the attention of a few giggling boys in the corner of the gym. “I know you guys are gonna be hustlers and pimps. Black people have always been hustlers and pimps. But get out of there as soon as you can. You’ll get hurt. You’ll get killed. Take advantage of this building. I know everybody says, ‘When I was comin up’ but when I was comin up we didn’t have this. Use it, get some books in here and read. It’s going to be hard. It’s hard now. You can’t go down to Ford or General Motors and work, they’re laying off now. It’s hard on your parents and it’s gonna be hard on you.”

The writer of this article, who may never have seen Jabali play, closed the article by saying that there was more to Warren Jabali than “a ball and an iron ring.” He felt “the man had a gift.”

It is now twenty-five years since that article was written, twenty-five years, or nearly so, since the ABA disbanded. I do not know what Jabali is doing today. The last I heard he was teaching in an elementary school in Miami. If he is teaching, I wonder if the children with whom he now works, or his fellow teachers, or his own children for that matter, have any idea of the regard with which he is held in certain circles. In Kansas City, there is an entire cohort who speak of him with enormous respect. The mere mention of his name conjures a time that shines far more brightly because of his presence in it.

This brief tribute is a way of remembering, a way of saying thanks. Whatever Jabali is doing today, I hope it is something that allows his spirit to soar. He was something special. For many of us growing up in the Kansas City area, his play gave us a vision without which, I believe, we would have settled for less in ourselves. I thank him for that. He was a player’s player and by his play would-be players like myself were inspired out of our limits.

David Thomas

———————————

Warren Armstrong Jabali died on July 13, 2012, a month before his sixty-sixth birthday.

In July of 2019, as mentioned above, I published JABALI: A Kansas City Legend. It tells more of Warren’s story and includes the above essay plus two essays that Warren wrote as well as descriptions of projects that Warren and I did together.

Midnight Basketball and Education panel, Crown Center, Kansas City, MO — 1999. Seated at the table: Alex English (NBA Hall of Famer), Jabali, myself, David Whalen, Carl Boyd: moderator. (Apologies to individuals not identified.)

———————————

In December of 2010, an event was held in Kansas City, MO entitled, “The Odyssey of Black Men in America”. It was attended by approximately one hundred men. At that event, Warren discussed how he may have been the first player to dunk from the free throw line (see below — video not to be used without permission).

The story of that event is detailed in JABALI: A Kansas City Legend.

———————————

There were two funerals following Warren’s death. One (the first) was in Miami where Warren had lived since his playing days ended, and the other in his beloved Kansas City where he had hoped to live the remainder of his life. The following eulogy was given in Kansas City.

Eulogy for Warren Armstrong Jabali

I’m very grateful to have the opportunity to speak today. Here is what I would like to say: Warren Armstrong Jabali was the first movie star I ever saw.

I was a sophomore in high school sitting in the bleachers and Warren was on the court. From that moment on, I never saw him play—in high school or the pros—but what it didn’t seem to me that the camera was on him. Thank goodness so many individuals came together (45 years after Warren played there) to make sure that the court at the Interscholastic League Field House—the court that he made immortal—bears his name. I can only hope, as my wife, Paula, suggested, that during the coming season they will find a few moments to dim the lights in his honor.

The last time I was with Warren was this past December. We spent two full days together visiting his old friends, his old haunts, the house in Kansas City, Kansas, where he grew up, the field that was once the Dunbar Courts, the Sportman’s Barbershop. We talked about his life and about life in general. Every minute I considered a privilege.

As he drove, I asked questions. “Warren, what about that story Al Smith tells concerning who would be the starting point guard for the Denver Rockets?” Al had been the sixth man with the Rockets. When Larry Brown was traded to Carolina, Al thought he would be moving to the starting lineup. Then the Rockets acquired Warren. For two weeks in training camp, Al battled Warren for the starting position. Then, Warren said to him, “We need to talk.” According to Al, Warren said, “Look, here’s how it’s going to be. I’m going to start and you’re going to come off the bench. That’s the way this needs to work.”

When I asked Warren about this story, he said, “Yeah, Al tells that story but I don’t ever remember doing that.” “Don’t you think you would have done that?” “No, I don’t,” he said. “It seems out of character.”

When I told Al what Warren said, he could not stop laughing. “Warren was very direct,” Al said. “He intimidated a lot of people who didn’t want to hear the truth as Warren saw it. But he was right and that’s the way it was. Warren started and I came off the bench.”

“Warren, why did Alex Hannum call you the smartest player he ever coached?” Almost irritated with the question, Warren replied, “I don’t know why he said that.”

Then, after a moment, he told the following story: “We had a big man on the Rockets who was always complaining about the fact that Ralph Simpson, the other guard on the team, would never throw him the ball. Simpson would shoot instead. Finally, I said to him: ‘Look, when I’ve got the ball and you’re open, I’ll throw it to you. You know that, right? But when Simpson has the ball, he’s going to shoot it. You know that, too, right? Well, then, why don’t you get your big rear end over to the other side of the basket where you can rebound in case he misses!’”

He then added, “I noticed at the time that Alex Hannum overheard me say that. It might have been that kind of thing that led Alex Hannum to say what he said.”

One of the places we stopped during our two days together was Coach Jack Bush’s house. Among the things Jack Bush talked about that day was his ongoing struggle with the game of golf. Try as he might, golf is the game he could not master.

I asked Coach Bush what he hoped his legacy would be. He said that he hoped it would have to do with his effort to shape the lives of young men. It was a thoughtful answer and left the room quiet for a moment. Then, Warren, whose timing was always so good, said, “That’s a relief. For a moment I thought he was going to say that he wanted his golf game to be his legacy!”

While on our drive, Warren went to considerable length to explain to me the difference between his game and the game of another Kansas City legend, Ernie Moore. His (Warren’s) game, he said, was about power. Ernie, on the other hand, was an artist. When we met up with Ernie Moore, Warren again explained the differences between their games. Ernie listened attentively. “(You) were artistic, also,” he said.

Several years ago, I posted a tribute to Warren on the Internet. In response, I heard from people from all around the world. In one case, an attorney for a former ABA player contacted me. The former player had a secret. Throughout his time in the ABA, he could neither read nor write. And it was Warren, he said, who had his back. For this the former player was extremely grateful. He was now literate and wanted to write a note of thanks to Warren in his own hand.

What is the story we are paying tribute to today? It is Warren’s story, yes, but what is that story? The hero, we are told, has a thousand faces, a thousand different names.

Here—in Warren—was the young man with extraordinary gifts who set out to share those gifts with the world only to discover that the world is out of balance and must be put right. And so, he engaged in the struggle to put things right. Along the way, though it took time, he found the love of his life. He had children and grandchildren who he adored. And always, there was the effort to put things right.

“What are you interested in?” I asked. “I mean, you have Mary and your family, but after that, what are you interested in?” “Only one thing,” he said, “the struggle of Black folks.” “The struggle of Black folks,” I repeated. “Yes,” he said, “the standing of African American people in the human community.”

Warren engaged in the struggle to put things right. And he did change things, many things. Already there is talk of naming the grade school where he taught for thirty years in his honor. But also, in the process of changing things, he, too, was changed.

In Mary Beasley’s beautiful book, Shattered Lens, she devotes much of the last two chapters to the love she found with Warren—in particular, to when they were courting.

This is Warren speaking to Mary:

“I’ve traveled around the world. I’ve met many people and I’ve done almost everything I’ve wanted to do. I now want you to be fulfilled. I am very content…”

And then he added, “I want to learn to get along perfectly with one other human being. That’s my spiritual goal. I want to love and be loved intensely and unconditionally.”

I sometimes have had people say to me, “You make too much of him. You overstate the case.” No. It is just the reverse. They failed to see what was right in front of them. I am so very grateful that I grew up in this city during the time of the great Warren Jabali. His kind is remarkably, amazingly, sadly rare. We mourn our loss when such individuals depart, but we treasure their impact on us. They mark the path. They call us to a higher standard. And they put wind in our sails. The hero has a thousand faces, yes, and one of those faces is the face of Warren Edward Armstrong. The hero is known by a thousand names and one of those names is Jabali.

David Thomas

July 28, 2012