The Healing Art: Elizabeth Layton

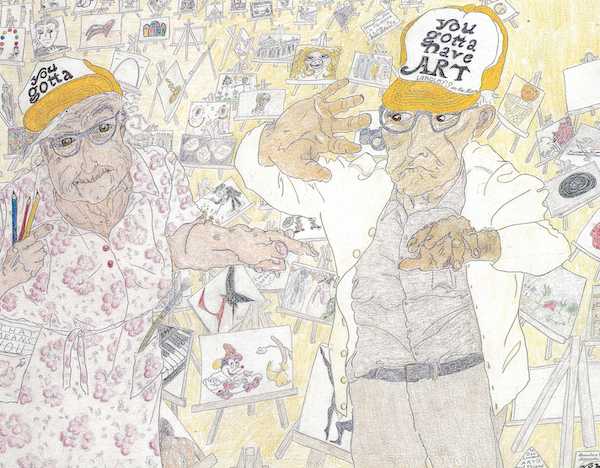

I met the Layton’s in the early eighties. Friends who knew them and knew of Elizabeth’s work encouraged me to contact them.

At the time, I was attempting to put together a series of artworks (slides of artworks) to use in a workshop on imagination and creativity. In response to my letter explaining my purpose for writing, Elizabeth sent me slides of her work along with her permission to use them as I liked.

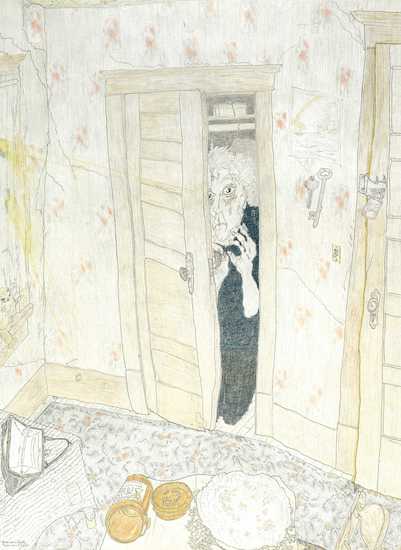

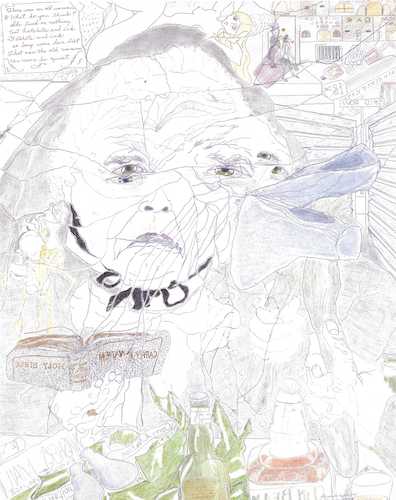

I know of few things more inspiring (and magical) then the exorcising of one’s illness through art. This is what Elizabeth Layton did, her story now widely known in art therapy circles. Beginning at the age of sixty, with the help and support of her husband, Elizabeth began drawing.

Through art or war

In Ernest Becker’s Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Denial of Death (the book Woody Allen was holding in the bookstore scene in “Annie Hall”), Becker wrote: “Release your neurosis through art or war, that is your only choice.” By “neurosis”, he meant (perhaps) “having feelings and emotions that interfere with your ability to accomplish your purpose”. That, at least, is how ethicist John David Garcia defines the term.

If, for example, you release your neurosis through war, then the damage done to you by this world is returned to the world, to those around you, wherever you can find a suitable victim. Should you survive your warlike aggression, survive it with some degree of sensitivity and self-reflection intact, then guilt and perhaps self-loathing will be the result. On the other hand, if you release your neurosis through art, then the result is twofold. On the outside there will result a work of art, a painting, a garden, an artful exchange between people; and on the inside: an increase in self-worth and wellbeing.

The Wind Harp

The analogy here is to the wind harp, the instrument that so fascinated the romantic poets and about which Owen Barfield writes so beautifully. The wind harp was so designed—legend has it—that wind, entering the instrument from one side, exited the other side as music. So it is, said Coleridge, we are all wind harps, or may choose to be.

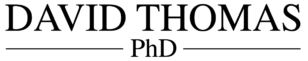

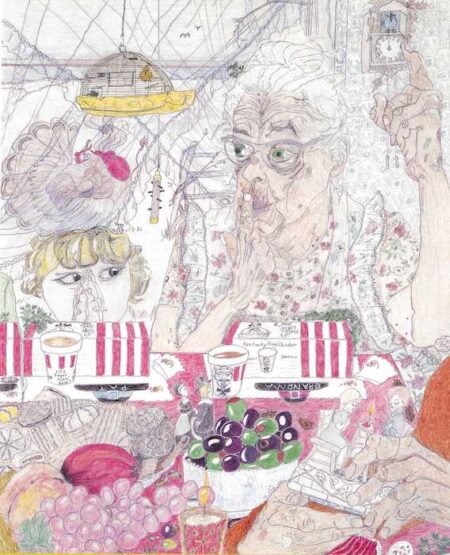

This is all by way of describing what Elizabeth Layton did in her own life. An early divorce, several stays in a psychiatric institution, shock treatments, the death of a child, all transformed through art into some of the most richly filled drawings in contemporary art. Never have I seen the stacks of correspondence that I have seen in the Layton home, all from people who had their lives enriched by her work and were moved to write. As for her depression… “I don’t know why it is,” she wrote, “but this contour drawing has completely cured me of my forty-year depression. I simply don’t have it anymore.”

Genius and beauty

“All of us,” said Nietzsche, “are potentially hero or genius, only inertia keeps us mediocre.” In many respects, depression and inertia are the same thing; to suffer from one is to suffer from the other.

Movement is perhaps the essence of all treatments for depression, movement from one place, activity or viewpoint to another; and when the movement is under way, the focus turns to form; and then, as Becker said, to art. The result, if you persist, as Elizabeth Layton did, is the gradual accumulation of legitimate reasons for liking yourself, for respecting yourself… to the point that the potential of which Nietzsche spoke has a chance of being realized.

“I believe that Layton may be a genius,” said one New York art critic reviewing an exhibit of her work and another, writing independently, concurred. And although Elizabeth Layton shied from such comments, she did reveal in a different context another outcome of her work. While reviewing slides of her early drawings, she commented: “You know, in the beginning I drew myself as someone who was ugly but I don’t see myself that way anymore. Now I draw someone who is beautiful.”

“ …this Right Side of the Brain living, accompanied by drawing of mirror images of impressions and feelings, has completely cured my 40 year old depression. I never have it any more… I started drawing in September ’77 and in July ’78 I suddenly said, ‘My depression is gone.’” — letter to D. Thomas

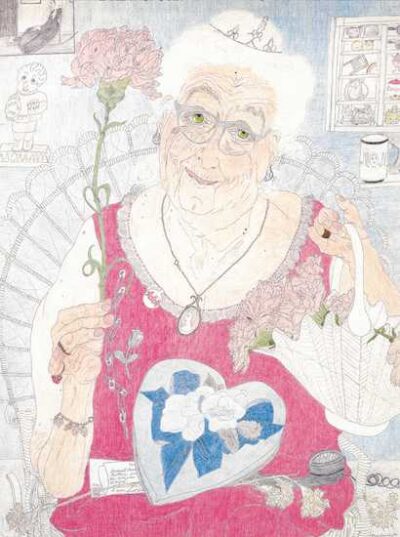

In a letter I wrote to the Layton’s I enclosed stanzas from the Wallace Stevens’ poem, “The Man with the Blue Guitar.” In that poem, “things as they are” change whenever they touch the blue guitar. The last line of their reply: “We loved ‘The Man with the Blue Guitar.’ Glen says to tell you he has a brown ukulele!”

Reviewing slides of her work, I asked Elizabeth: “A lot of your drawings deal with pretty tough topics. What do your neighbors here in Wellsville think of your drawings?” Elizabeth replied, “Well, I don’t know. Glen, what do the neighbors think?” “Well,” he said, “it’s controversial.”

—————————–

Elizabeth Layton died March 15, 1993. She was 83. Glen died two years later. Exhibitions of Elizabeth’s drawings have appeared throughout this country and as far away as Paris.

(For more on the life and work of Elizabeth Layton, see The Life & Art of Elizabeth “Grandma” Layton by Don Lambert: WRS Publishing, 1995.)

Gallery

David Thomas, PhD