Wildness & Deep Ecology: Roger Ross Gipple

Photos by Beth Ann Shatava

I have been in dialogue with Roger Ross Gipple for nearly forty years. He is a wonderful conversationalist. He knows what he thinks and he thinks deeply. I believe it is fair to say that throughout his life he has pursued a single theme though its name has changed over the years.

Acquiring our alliegences

Mr. Gipple grew up in a small town in Iowa. He took into himself the life of his community, a community that extended beyond its people to the land, forests and water systems that make rural life (all life) possible.

To put it another way, Mr. Gipple was mentored by the interweaving of small town life with its land use and farming practices. He also was mentored by a magical fellow named Emil Glade.

“Emil Glade was a mentor to me and in important ways was like a grandfather. He took me on many adventures, taught me his way of farming and caring for the land, of working and doing business, of helping people and having fun. We often went to his woods, not to hunt or fish, but to walk and talk or just sit. Emil loved his life and the people in it. I think of him today. I will not forget him.” – R. Gipple

It’s interesting how our allegiances are shaped early in life, not always but often. We get our commitments before we know it, though we may travel great distances before we come to serve them fully.

Mr. Gipple attended the University of Northern Iowa… a degree in business with an emphasis in marketing. In ’71, he formed with a partner an Ag recruiting firm, selling his part of the firm in ’79. Then, in 1980, he formed Property Stewards, a company providing farmland brokerage and management services.

The dark night

Property Stewards was very successful, as successful, certainly, as Mr. Gipple cared to make it. Then, unexpectedly, came the dark night of the soul: divorce, the farm crisis of the mid-80s, and cancer.

I have learned a great deal from Mr. Gipple. He has a laser focus, a capacity to sustain his effort with little in the way of outside support.

By 1993, through focus and sustained effort, Mr. Gipple had recovered both financially and physically. The blows of the ‘80s were behind him. He was fifty. A challenging time had passed affording an opportunity for renewal and a new commitment.

Mr. Gipple told me that he thought again of Emil Glade. He remembered the way in which Emil Glade was at ease with himself, how he appeared to have a seamless, peaceful, organic relationship with the life he had created. He also thought of his Uncle Floyd, a man who in his nineties surprised Mr. Gipple by remarking: “We never should have straightened the rivers.” It was a remark that contributed to Mr. Gipple’s developing view that Nature is more than a provider of resources.

Wildness

Intuitively, Mr. Gipple was drawn to the concept of wildness (“We never should have straightened the rivers”). With that concept alone he could address his various environmental, agricultural and lifestyle concerns. Wildness as opposed to domestication, the latter being what has happened in the extreme to the state of Iowa, to the country as a whole, possibly to the human spirit.

Mr. Gipple defined wildness as creating space in oneself and in the environment for spontaneity to flourish… a theme akin to James Carses’ “freedom to be natural”. In Mr. Gipple’s formulation, wildness means: self-reliant, spontaneous, self-willed, self-regulating, local, authentic, and free.

The conversation

If I were to imagine the conversation Mr. Gipple most wanted as he formulated his view, it would be something like the following:

Over-domestication is the problem and “wildness”, the solution…that’s what I’ve come to believe. We’ve evolved practices as a culture that are simply unnatural, damaging. Owen Barfield called it “cutoffness”. Many of us feel cutoff from the natural world, and in a sense, that means cutoff from ourselves. The spirit suffers… What is lost by the bluebird when caged? It is its color. Can we not at least entertain this thesis, that what I am calling “wildness” is fundamental to our wellbeing?

It wasn’t as though Mr. Gipple could not find kindred spirits. There was Thoreau: “Dullness is but another name for tameness. …all good things are wild and free…”; the poet Gary Synder: “…self-realization, even enlightenment, is another aspect of our wildness.”; philosopher and theologian Joseph Priestly: “…the more liberty…given to everything which is in a state of growth, the more perfect it will become.”; conservationist Raymond Dasmann: “When we chain and confine all our wild country, eliminate the free-roaming animal life, then there will be no space left for that last wild thing, the free human spirit.” And others, as well: Scott Nearing, Aldo Leopold, Arne Naess, Alan Savory, James Carse.

These individuals, however, were available through books only. They offered spiritual support, not dialogue. It was with a small circle of friends gathered over years that Mr. Gipple found sustenance and support.

Philosophy into action

Acting on the implications of the wildness theme, Mr. Gipple returned parts of the farms he owned to wildness: tearing out fences, tearing down unneeded buildings, no livestock, no planting or grazing, the land left to nature. He placed hundreds of acres in a trust with the Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation so that they could remain untouched in perpetuity.

He also explored how best to use his financial resources to enlist others in the “conversation”. He offered grants to visual artists, poets, and filmmakers to create artworks that expand the reach of the wildness theme, artworks that take the theme in directions he, himself, had not considered. He financed the development of a social media presence offering a platform for others to get involved. In relatively short order, given how long he had waited, there it was, a conversation on the value of wildness involving artists, conservationists, scholars, farmers, and others.

Wildness and the self

All ideas for changing the world turn eventually on the self. You can extend your formula for change only so far before the formula turns around and asks: What about you? Can you be what you are proposing? Can you find indifference within your deep caring, enough at least so that you do not interfere with what will flower of its own accord?

For Mr. Gipple, the answer to these questions has come down to letting go. “The Wildness Initiative has required a great deal from me,” he noted, “but it now seems to have a life of its own. It may continue or it may not, I have no idea. But at this point, letting go is how I serve it best, and serve myself, as well.”

To find a cause, an involvement that contributes to the world but also contributes to (indeed, requires) your development as a person is very good fortune, indeed. Mr. Gipple would say that through his effort to serve the cause of wildness, he has gained as much as he has given. “The work,” he said, “has nourished my soul.”

I would not know how far the wildness concept reaches were it not for Mr. Gipple. Embeddedness, trust, “at homeness”, the poetry of life. It seems to me that it is a remarkable and important cause Mr. Gipple has chosen.

In his book, Wild Hunger: The Primal Roots of Modern Addiction, the philosopher Bruce Wilshire writes about “ecstasy deprivation.” Ecstasy is an intrinsic hunger, he writes, satisfied, in part at least, through connection (re-connection) with the wild.

“I thought I was living fully and happily–that I was writing freely and well–on that beautiful summer morning. But only when the wild bird arrived did I become aware of how limited I had been. My life expanded abruptly. What might I be missing right now, working and re-working this paragraph? It must be something like what the wild bird supplied.”

A body of work

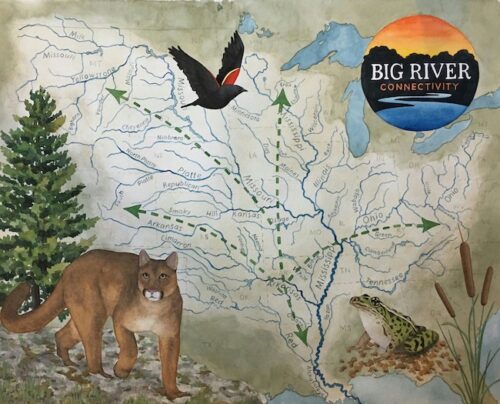

In order to refer the interested reader to a body of work I cannot summarize here, I recommend BeWild-ReWild / Big River Connectivity: https://bewildrewild.org. At this site you will find the many specific projects undertaken by a “loosely-knit (and growing) group of volunteers actively engaged in considering three questions: 1) What do you/we mean by wild? 2) What lifestyle changes are needed for us to live within the bounds of sustainability? 3) How can we create a wilder, more beautiful, more biologically diverse and more enduring Mississippi River Watershed?”

On the Facebook page, BeWildReWild, Mr. Gipple writes: “This page is a place for visioning, debating, storytelling, teaching, and learning on the subject of WILDNESS. One might say that we are specialists in REWILDING…, seeking personal liberation as we allow more freedom for that which lives around us. Our focus is unwavering… The BeWildReWild Vision of BIG RIVER CONNECTIVITY is for a wilder, more beautiful, more biologically diverse, and a more enduring Mississippi River Watershed.”

Another Facebook page of interest: Re-Wilding Iowa and Beyond.

Sky Cougar, Capitol View Elementary, Des Moines, Iowa – 2006; D. Dancer, artist; sponsored by Roger Ross Gipple

Photo by Beth Ann Shatava

“There is great mystery in wildness, out of that mystery comes great abundance. All life has value,” — Roger Ross Gipple

Roger Ross Gipple Radio Interview

David Thomas, PhD