Field Muralist: Stan Herd

Stan Herd is the father of the field mural.

He grew up on the family farm located not far from Protection, Kansas, a small community of 700 people in Southwest Kansas. According to Wikipedia, Protection “became nationally and internationally known via radio and television in 1957, when the National Polio Foundation chose it as the center for the free distribution of Salk vaccine shots for polio. Protection was 100 percent protected.”

Stan left the family farm soon after high school. Though he received an arts scholarship to attend Wichita State University (WSU), he did not remain at WSU long. Rather, he left to pursue his life as a full-time artist, which is to say, as a bartender (along with other part-time jobs).

Initially, Stan painted on canvas and did murals on the side of buildings. It was a flight over the Kansas landscape in the late 70s that gave him the idea of the field mural. The patchwork of colors on a relatively flat surface meant that an artist could operate on a grand scale providing the artist had the knowledge and skill to do so.

Stan had the knowledge. He knew the grasses and the crops that grow in Kansas soil and the color they provide throughout the growing season. And he had the skill. Not just the knowledge of perspective and composition he had acquired as a painter, but the skills required to work on such a scale, i.e., the ability to operate tractor, plow, disk, and the other equipment.

The Field Mural

By 1981, Stan had completed his first work: a 160-acre portrait of Satanta, war chief of the Kiowa. It was a portrait that could be seen from 30,000 feet above the earth. Another portrait soon followed. This one, similar in size, was of Will Rogers.

Other projects—some commercial (allowing Stan an income) and some purely artistic—gave traction to Stan’s career. One project of note, located in New York City, was entitled Countryside, a one-acre landscape in the style of Thomas Hart Benton.

Countryside, along with the process involved in creating it, was the subject of an independent film by Chris Ordal. Called Earthwork, it starred the Oscar-nominated actor John Hawkes as Stan. As Wikipedia puts it: “Earthwork tells the true story of Herd’s transformation of a large, trash-strew, barren lot near a graffiti-laced underground railway tunnel inhabited by the homeless, into Countryside.” The film was shown at film festivals around the country and has won several awards. As an aside, Stan was not paid to do Countryside, but he was aided by the homeless living nearby. They weeded, planted and protected the work in Stan’s absence.

Perhaps the best way to introduce Stan is to share his work. Here is a sampling:

The above works are temporary, typically lasting a growing season. Stan has also done permanent installations.

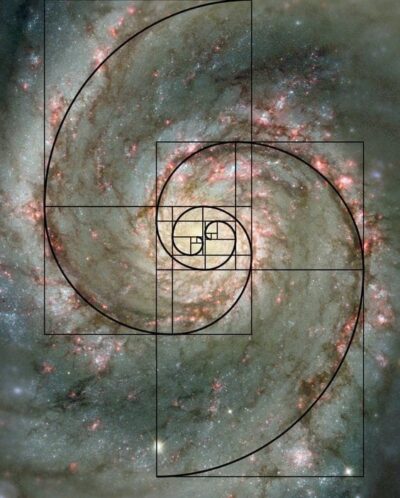

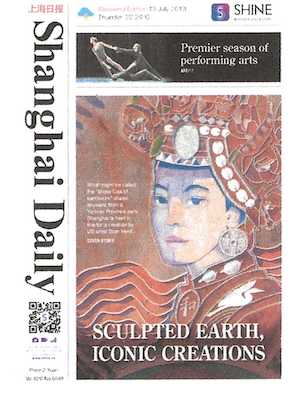

The most recent example of a permanent installation is his “Young Woman of China”. This work, located on a hillside in the Yunnan Province of Southwest China, is four and a half football fields in size and consists of marble, granite, natural stone, rice paddies and other material native to the region. (Two images follow: 1 – work in progress with road and workers to provide a sense of scale, and 2 – close up of completed image.)

Part II

I have known Stan since the mid-70s, and I have always been an admirer of his work. We have often discussed the prospect of doing a project together, one that would involve our mutual friend, Daniel Dancer (see ART FOR THE SKY).

I outlined such a project in Poster 3 (see POSTER SERIES). The idea was to create a field mural depicting a region’s vision statement, a large and dramatic image conveying the process that helps secure a sustainable and just future. This image would be permanent (not so permanent that it couldn’t be modified in accord with the wishes of the people of the region) and visited on an annual basis by thousands of school children and community members to remind them of the vision for the region and to enjoy a “festival of learning”. The project is discussed in greater detail in Poster 3.

The Fibonacci Project

Poster 3 got the conversation started. What emerged—proposed by Stan with some features of the “vision statement” proposal intact—is the Fibonacci Project.

Stan conceived of the Fibonacci Project in the spring of 2019. If completed as envisioned, it would be his most ambitious project to date, involving permanent companion earthworks in both China and the United States.

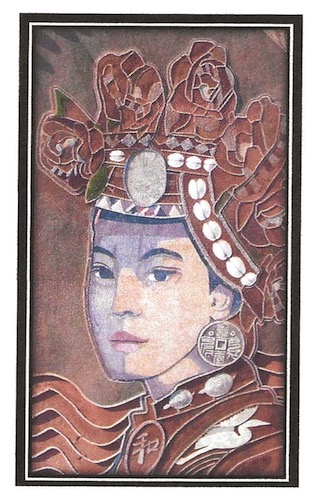

What is the Fibonacci Project? First, it is important to understand the Fibonacci sequence. It is a numerical sequence that seems to underlie the growth of many relationships in nature, in particular, the growth of the spiral. Sea shells, trees, flower petals, storms, galaxies, from the micro to the macro, all to a remarkable degree adhere to a specific ratio, the golden ratio as it is sometimes called, i.e., the Fibonacci sequence.

Since its discovery, the Fibonacci sequence has fascinated scientists, artists, architects, musicians, and others as it seems to suggest the rule by which nature unfolds into arrangements that reveal both proportion and beauty.

The Fibonacci Project, as currently conceived, involves the creation of two large earthworks—one in China, the other in the United States—each mirroring the Fibonacci sequence (the Golden Ratio). These earthworks would be “sculptural”, with thirty-foot stone pillars marking the curve of the spiral. They would be works of art to be seen from the air (revealing beautiful patterns of landscaping, shadow and symmetry) as well as parkland and garden for individuals on foot to enjoy.

Below are three AI generated images of a Fibonacci earthwork.

These earthworks would also set the occasion for international exchanges. Artists and others from each country teaching and learning the best of what each country has to offer.

In addition to exchanges between nations, each earthwork could provide the site for an annual “festival of learning”, an opportunity for thousands of children and community members to participate in creating colorful patterns and images on the floor of the artwork in addition to attending workshops focusing on the development and wellbeing of individuals, families, and the region overall.

The Benefits:

— The earthwork would be a signature image for the region, drawing national attention

— The earthwork would help instill desired values (implicitly so, but explicitly as well via international exchanges and festivals of learning)

— The creation of the earthwork would be an exercise in community building, i.e., in the collaboration required to achieve a shared vision

— The earthwork would promote values that serve the long-term health and vitality of the region.

At this point, it’s unknown whether or not this project will happen. Funding is the issue and also, securing the location for the earthworks in both countries. For updates on the Fibonacci Project or on Stan’s work, contact Stan Herd at [email protected].

David Thomas, PhD