Science & Lifestyle: Keith & Ocoee Miller

I went to the University of Kansas in 1974 to study with L. Keith Miller.

The Human Development Department at the University of Kansas was, at that time, the top applied behavioral program in the country. Don Baer, Montrose Wolf, Todd Risley, Jim Sherman, Keith Miller and others were shaping a field characterized by the experimental analysis of behavior. They were doing research and building programs that were making a meaningful difference in people’s lives.

While living in Denver, I helped create a national conference on behavior modification. I knew of Keith’s work and I made sure that he was among the invited speakers. We spent time together and it became clear to me that I could learn from him. I asked if he would take me on as one of his graduate students and fortunately, he agreed to do so.

Graduate School

I spent five years in the Human Development Department at the University of Kansas. It was a wonderful time of life and at its center was my working relationship with Keith.

In time, there were other professors in the Human Development Department who spent time with me; in particular, Montrose Wolf (thank you, Mont) and to a lesser extent, Don Baer and Jim Sherman. Also, there were professors in other departments who engaged me in dialogue and who allowed me to be their student and friend. I can’t say enough about what a privilege and pleasure it was to be in the Human Development Department, to be at the University of Kansas, to live in Lawrence, Kansas.

What I did not know when I signed up to study with Keith is that I would be getting two for one. Keith’s wife, Ocoee, was often a part of our discussions, increasingly so as the years went by. Her thoughtfulness, insight and life experience added wonderfully to the quality of the dialogue I enjoyed with them both.

A technology for cooperative living

In my opinion, Keith’s professional interests are twofold. First, the egalitarian community; specifically, how to build societal arrangements where unfair advantage does not accrue to any one person or group and where opportunity is distributed equally.

How to build such an arrangement?

For many years, Keith’s research setting was a student housing cooperative, a large house where over thirty students lived at any one time. There, Keith and his graduate students attempted to create a community of shared responsibility.

The housing cooperative offered the following invitation: Looking for a place to live? Perhaps this is the place for you. However, before deciding you should acquaint yourself with the values of the cooperative and to how these values are put into practice. Work is shared equally here and it is inspected since work must be done to a specific standard. Leadership and decision-making are shared, as well. You are expected to participate. Residents hold one another accountable for the health and smooth functioning of the community. You grow as a person when you live here but it is not for everyone.

Keith and his graduate students, some of whom lived in the cooperative, worked with residents to developed practices anchored to fairness and shared responsibility. Cleanliness, food preparation, decision-making, meeting procedures, rental adjustments based on resident performance and more were aspects of community life. Importantly, every effort was made to validate experimentally the effectiveness of each new process or procedure. The immediate or short-term goal: building a community that could be student-run without a loss in quality of daily life. The long-term goal: a technology for cooperative living.

Keith’s research on cooperative living is, in my opinion, among the most interesting and relevant to the demands of modern life of any in the field of Applied Behavior Analysis.

Making a lasting difference

The second of Keith’s professional interests is difficult to separate from the first. How do you build programs that survive beyond the involvement of the person who developed them? The developer leaves and the practice, though proven effective, is abandoned or gradually fades from use. Keith’s interest is in making sure that beneficial practices are maintained and perhaps evolved by those who remain in the setting.

Put another way, and this is the reason I was so drawn to his work, Keith’s focus is on culture. Not on specific practices or interventions per se, important though they may be, but on ensuring that the culture in question (whether of classroom, institution or housing cooperative) continues to utilize practices that have proven beneficial. His focus is on building cultures that evolve. This puts his work in line with those scientists who envision an “experimental society”, a society in which science-based practices are evolved and made available for society to consider as it labors to further human development and human flourishing, overall.

A remarkable life

Ocoee Miller, like Keith, has lived a remarkable life. In the most recent chapter, now spanning twenty years, she became an herbalist. This required that she study the herbs and plants of eastern Kansas, that she understand their healing properties, and that she learn how best to prepare them for medicinal uses.

As an herbalist, she gave workshops and for many years took on a small number of students who spent the season with her, learning to identify and harvest medicinal plants and then, learning to prepare healing potions.

Ocoee never advertised. Awareness of her services spread by word of mouth. When her students urged her to put together a brochure, she declined. Though later, she did offer them “My Life in a Nutshell”, a listing of the key events in her life. I marvel at the fact that a single lifetime can contain all the experiences listed.

MY LIFE IN A NUTSHELL in no particular order

by Ocoee Miller

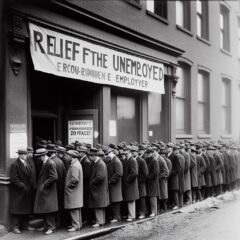

Born in 1938 in San Antonio Texas — Have vivid memories of Naples, Rome, Florence, Capri, Sorrento, Munich, Zurich, Madrid, Barcelona, Paris, Venice, Istanbul, Athens, Beirut, Cairo — Three times the house I was in was struck by lightning — My childhood heroes were Joan of Arc and Tarzan. I tried to be both — Have vivid memories of originals by Michelangelo, Raphael, DaVinci, Goya, Botticelli — Twice lived in buildings half destroyed by heavy artillery during WWII — Was expelled from nursery school for biting — Survived a house fire in Munich — Lived for almost a year (at age eight) in an Italian Riviera hotel with parents absent — Got tear-gassed in a hotel in Athens where a riot was happening just outside our hotel — Rode a camel to visit the Sphinx when it was the only way to get there — Have lived through four earthquakes, two of them were major — 1957 got married. Later had two children — Was fortunate enough to be able to attend two of the best schools in the world — Received medical treatment by a shaman in a tree

house in the Costa Rican rain forest — Had the good fortune to be born in the Great Depression of the 1930s — Have completed four vision quests — Was treated for Lyme Disease twice — Had a life-changing shamanic conversation with a tarantula — Was infected with six different types of parasites — Have been close to the mouth of three volcanoes: Vesuvius in Italy, Arenal in Costa Rica, and Kiluea in Hawaii where I looked directly into the caldera. I stepped back from the edge only when I realized my shoes were melting — Was privileged to become acquainted with gypsies — Visited the concentration camp Dachau before it became a tourist site. Forever traumatized — Survived Dengue jungle fever — Was mentored by several Native American medicine men and one Medicine woman — Had my life threatened numerous times — Had my office fire bombed with homemade napalm — Received the “Woman of the Year” award

from the Chamber of Commerce women’s group in 1975 — Had attended 19 schools by the time I graduated from High School — Had our phone tapped, our house ‘bugged’, probably by the FBI and/or the Klan — Have had four VERY close bear encounters in the wild. Bears scare me — As a very young child my toys were twigs, dirt and rocks, sometimes leaves — Had my home burglarized four times — Taken to jail, held but not booked — Have had serious food poisoning at least six times, once almost fatal — As a child I played in bomb craters in the German forest. Those holes were ringed with moss, violets and tiny frogs — Had as friends several hookers, a bank robber, a house burglar, two pimps, a con artist — Went to school with the man who grew up to be King of Greece — In 1979 I dropped out of everything, resigned from six boards of directors, moved with my family to the boonies and made myself as inaccessible as possible. Became an herbalist.

“All flourishing is mutual”

In 1979, as Ocoee indicates, she and Keith moved to the country. They built a house on a hillside hidden by the forest. Keith continued his work at the University until retirement while Ocoee managed a large garden and began her study of natural medicines.

The house they built is like a house one might find in Greece. Ocoee spent years in Greece and Keith has steeped himself in Greek history and, pertinent to his professional interests, steeped himself as well in the life of the Greek village. In a sense, both Keith and Ocoee are citizens of the Greek village. Quiet, sustainable, creative, the garden as metaphor, the forest as metaphor… the opportunity to contemplate the nature of things…the underlying ethic to which they often return summed up by Robin Wall Kimmerer in her remarkable book, Braiding Sweetgrass:

“If one tree fruits, they all fruit—there are no soloists. Not one tree in the grove, but the whole grove; not one grove in the forest, but every grove; all across the county and all across the state. The trees act not as individuals, but somehow as a collective. Exactly how they do this, we don’t yet know. But what we see is the power of unity. What happens to one happens to us all. We can starve together or feast together. All flourishing is mutual.” (p 15)

And its corollary:

“What I do here matters. Everybody lives downstream.” (P. 97)

I consider myself lucky to have Keith and Ocoee as teachers and friends.

Addendum

The following one-act play (can it be called that?) is dedicated to Keith and Ocoee Miller. In graduate school, Keith did his best to teach me how to think. His method was Socratic. To everything I said, he would ask: What do you mean? What follows is not offered as evidence of his success. Only as a playful expression of thanks.

Road Trip

Two men on a road trip. The opportunity to look through a shared windshield and, for the most part, carry on an uninterrupted conversation.

A: Frankly, it all strikes me as unbelievable.

B: What strikes you as unbelievable?

A: Everything. All of it.

B: OK.

A: Everything we see out there, and everything we see in here.

B: Your point?

A: My point, or rather my question: How does a person not live in continuous wonderment?

B: Is that where we’re starting?

A: It’s a long trip.

B: Well, for starters, you wouldn’t survive. You have to focus on what you’re doing. Otherwise, the semis will get you. They’re everywhere.

A: And, it’s constantly changing. That’s another thing. Some days I can’t stop marveling at it.

B: Good days, I would say.

A: Yes.

B: (summing up) So… fine. All very Buddhist… Is that it?

A: Then there’s the issue of inevitably… I wonder about that. Is it all simply unfolding or is there…

B: (interrupting) I think it’s just unfolding. I don’t see how it can be otherwise. What’s the expression? “…what’s found in the effect was already in the cause.”

A: No free will…

B: “…the stone in the air thinks it’s free forgetting the hand that threw it.”

A: It’s amazing, though, isn’t it? All of it leading to animals like us, capable of learning, loving, feeling regret.

B: If you’re asking me how it works, I don’t know.

A: (looking at the road and then off and on at B) Being sensitive to the consequences of your acts… that’s one of the keys, right?…so you can know if you should do more or less of what you just did when similar circumstances arise.

B: (nervous) You’re driving. When you talk to me you don’t have to look at me. Really, you don’t. I can hear you just fine.

B: (continuing after brief pause) There is a Buddhist notion that I have always liked… something like “the conquest of the self is the human being’s noblest triumph.”

A: That’s what I’m saying.

B: That’s what you’re saying?

A: We were talking about freedom, right. Free will… we dispensed with that… But freedom…

B: As in…

A: You learn how to be free, just like you learn any number of other things. You’re not born with it….

B: Just like you learn any number of other things?

A: Yes, just like you learn any number of other things. You acquire it gradually, over time. You learn how to use tools, right. Language comes along. You learn to manipulate not only rocks and stones, but symbols and numbers. You interact with the environment to your advantage. You’re a problem-solver. Gradually, you gain understanding. Knowledge of how things work. Awareness. Consciousness.

B: Consciousness?

A: Of more and more you become conscious. You continue because there is advantage in it… for you. your family… your tribe. And so it goes: Advantage or survival value in toolmaking, in language, even in the formation, eventually, of a “witness”, the ability to observe yourself, to notice what you notice… The environment writ large giving birth to an organism that is aware, conscious, and to a degree, free.

B: Where, if I may ask, is the freedom in all of this?

A: Well, obviously, it’s a special kind of freedom… maybe that’s not the right… no, freedom is the right word.

B: (pointing to the crowded road) Be careful where you’re going?

A: When I look at myself, you know what I see?

B: Not a clue.

A: I see a feather for nearly every wind that blows. It bothers me. I think about it a lot. Too often I lack the steadiness to stay the course. Those temptations…

B: Every profession I know of talks about this problem.

A: Well, the freedom worth talking about, maybe the only freedom there is comes with the capacity to forego the pull of the immediate or short term for the sake of something long term, a goal, for example, a dream, an ideal. That’s a beautiful thing, that degree of freedom.

B: John David Garcia, you know who I’m talking about, right?… he defines neurosis as “having feelings and emotions that interfere with your ability to accomplish your purpose.”

A: Yes, exactly. The free person has overcome his neuroses. In the extreme, the free person can conduct himself in accord with a fundamental ideal, honor, let’s say, or kindness or love (see the remarkable work of Howard Rachlin: The Escape of the Mind).

B: Triumph over the self…

A: Yes.

B: Well, why not?

A: You establish a pattern of behaving. That seems to be key. A pattern of choosing, of course-correction consistent with your grand ideal (or value) and gradually, eventually, you begin to embody that ideal. Not always, of course. But increasingly. No longer so vulnerable to the feelings and emotions and temptations that keep you from behaving as you would have yourself behave. Yes, triumph over the self.

B: A mouthful.

A: Don’t get me wrong. I’m not suggesting anything mysterious. Like I said, you acquire your freedom just like you acquire so many other abilities: courtesy of your interaction with the environment… education and training in the broadest sense. It’s just that now, so far, we aren’t very good at delivering this kind of education to ourselves or others.

——— (pause)

B: So, what about the Much-at-Once that William James talked about?

A: Back to where we started…

B: Yes. The awe and wonderment.

——— (pause)

A: Responsibility used to be spelled “response-ability”. Maybe we lack the ability, the freedom and self-control we just discussed. The beauty and wonderment of the Much-at-Once is glimpsed on occasion, but our experience of it dissolves as we are pulled and distracted by our neurotic concerns.

B: And the semis?

A: Yes, You are right. But we could be experiencing the wonderment and awe more often than we do. Sometimes we are in our own way. So preoccupied that we forget where we are, where we live.

B: Come again…

A: I had a friend who was always asking me if I knew where I lived.

B: “Do you know where you live?”

A: That’s what he would ask.

B: I know where I live. You don’t know where you live?

A: William James said: Every instant is lived in the Much-at-Once. That’s what we forget. I think that’s what my friend was getting at. We’ve forgotten where we live. And yet, open your mind, your senses, relax and suspend your formulations… and there you are… where you live.

B: This is a bit abstract, don’t you think?

A: Well, maybe. No. I don’t think so.

B: We missed the turnoff. Too distracted, right? There’s a Welcome Center up ahead. Maybe someone there knows how we can get where we’re going.

—————-

David Thomas

“The only conception of free will that remains meaningful in modern scientific psychology is this conception: When people act for the long-term good of themselves and their society, in cases where such acts conflict with their immediate and individual pleasures, they may meaningfully be said to be acting freely; …A person who does this is free from particular influences in the same sense that an ocean liner is free from the influence of small waves.” — Howard Rachlin, The Escape of the Mind

And this as perhaps a companion theme: “They seem free not in the sense that they go around breaking the laws of nature…but in the sense that they never find the natural order frustrating.” — Houston Smith, The Religions of Man