Historian: William M. Tuttle, Jr.

I met Professor Tuttle in the mid 1970s and since that time we have spent many hours together. He is a remarkable person.

“There is no progress without struggle,” Professor Tuttle would often say, quoting Fredrick Douglass. “Struggle is a never-ending process. Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it in every generation.” (Coretta Scott King)

Professor Tuttle’s career has been spent at the University of Kansas with stints at the University of Wisconsin (where his career began), Harvard, Stanford, and the University of California at Berkeley. His focus throughout his career has been on teaching and research, primarily (but not exclusively) in the area of African-American history. He has readied graduate students for teaching and historical research, and he hosts prominent scholars as well as political figures when they visit the university.

Early Influences

As mentioned above, Professor Tuttle’s focus as a scholar has been largely on African American history, and in particular, on the Black struggle. Reflecting on how he became interested in the Black struggle, Professor Tuttle writes:

“I grew up in Detroit. Detroit was rigidly segregated, and it was brutal in its treatment of Black men, particularly the ‘justice’ handed out by the Detroit Police Department, which was still 85 percent white at a time when the city had a majority Black population. My public high school of 4,000 students was all-white. There was a vast expanse between the races; I didn’t know any Black people.

“In fact, it wasn’t until the early 1960s, when I spent three years as the training officer of an Air Force bomb wing, that that changed. A very close friend was Captain Woody Farmer, a Black B-52 pilot who was killed in a mid-air explosion of his airplane. My commanding officer, Captain David Taylor, also was Black. He and I talked a lot, particularly about his boyhood in the South, his dreams for his own children, and the promise of the Civil Rights Movement to change America.

“I deeply admired both of these men, not only how they did their work but how they carried themselves as men. By word and deed, they became two of my most important teachers.”

(The talk from which the above is taken can be found in JABALI: A Kansas City Legend.)

Contributing to the Historical Record

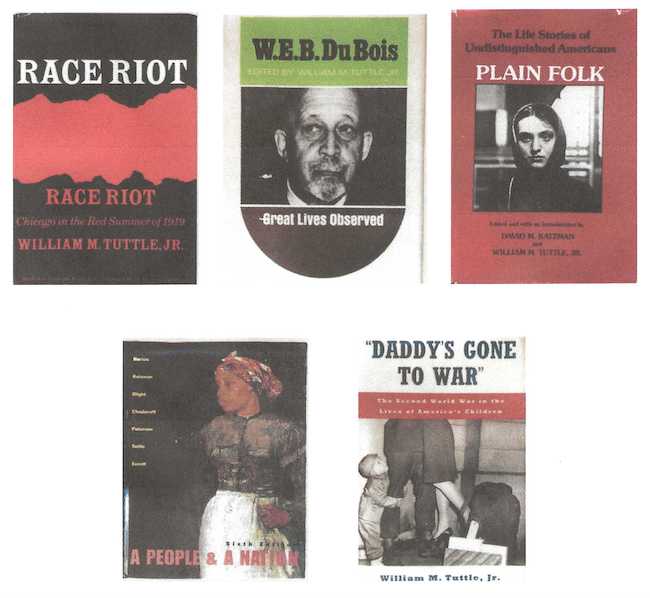

Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919 was Professor Tuttle’s first book. Drafted while in graduate school, it documented the racial animosities that led to the Chicago riot of 1919. It is a book that remains in print and its influence helped establish Professor Tuttle as an important scholar in the field of African-American history.

Other books followed: W.E.B. Du Bois (an edited volume in the Great Lives Observed series); Plain Folk (with David M. Katzman), where history is told “from the bottom up” through the stories, voices, and perspectives of common people (rather than through prominent and powerful figures as is so often the case); A People and a Nation, a history text written with other historians that “highlighted the dramatic changes taking place in the writing of social history, such as African American history and women’s history” – again, as with Plain Folk, history told from the bottom up; Daddy’s Gone To War: The Second World War in the Lives of America’s Children, nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in History, this book combines social history and developmental psychology. Its focus: the impact of absent fathers on children growing up during the Second World War. Again, history told by giving voice to the common people who lived it. Finally, and most recently, World War II and the American Home Front (with John W. Jeffries and others), in which the focus is on “how ordinary men, women, and children reacted to sometimes overwhelming population movements, to the absence of fathers and brothers in the military, to massive, if temporary, changes in women’s roles, and to the all-pervasive presence of the war in popular culture.”

Professor Tuttle is the recipient of numerous awards: the 1998 W. T. Kemper Fellowship for Teaching Excellence, the H.O.P.E Teaching Award from the Senior Class of 2001, and the Chancellor’s Club Career Teaching Award in 2004. In 2007, Professor Tuttle taught at Radboud University in Nijmegen, The Netherlands, holding the John Adams Distinguished Fulbright Chair. He has lectured in Cuba and Japan as well as in the Netherlands, and he is the recipient of the Higuchi Research Achievement Award and The Steeples Award for Service to Kansans.

History, Culture and Age

Briefly, I would like to reflect on what I have always considered a pivotal decision made by Professor Tuttle in the course of his career; namely, to make the twentieth century through to the present his timeframe of interest. African American history spans four centuries and while that history is known to Professor Tuttle and informs his work, he nevertheless picks up the story in the twentieth century with the race riots of 1919. With Daddy’s Gone to War, the timeframe narrows further. Here, Professor Tuttle turns his attention to the timeframe of his own life, 1930s to the present. To make the focus of your scholarship the time period through which you are living and to tell history from the “bottom up” has always struck me as enormously wise. It makes everyday life subject matter. You look into the life that is being lived in front of you for what it reveals about the time through which the people you know and don’t know are living. You see history reaching into daily life, what it limits and constrains and what it makes possible.

It is no wonder that Professor Tuttle should wind up a student of human development. No wonder that he should formulate an overview that sees the confluence of history, culture and age as key to understanding human development and social change. Much can be said of his formulation, far more than can be discussed here, but in brief (with apologies should I be stripping the formulation too bare): history delivers its events, culture interprets those events (perhaps buffering their impact), the age of the individual at any given time influences the developmental imprint left by those events. Of course, history, in turn, is made by individuals, as is the culture of which they are a part…and so, the process continues. Not historical inevitability unless, perhaps, we fail to wake up to what is influencing us to behave as we do.

Professor Tuttle (from Daddy’s Gone to War):

“Human Development, as well as social change, often proceeds in fits and starts. Sometimes it is linear, sometimes orderly. Frequently, however, its movement reflects the chaos of its major elements—age, culture, and history—which are constantly shifting and realigning.”

“…Historians and developmentalists share a commitment to the study of human life, and from examining the American homefront, it is evident that the Second World War’s effect upon children varied widely depending up the child’s developmental stage.”

“…Children have never asked to be born into situations of war, and yet they repeatedly have been, and they have suffered whether in the war zone or on the homefront. And it is because of adult’s repeated mistakes that children, who understand war least, have been so deeply marked by it. For their sake, as well as our own, we must strive for enlightenment in reversing history.”

The Bill Tuttle Distinguished Lecture in American Studies

Upon his retirement, a celebration of Professor Tuttle’s career was held in downtown Lawrence, Kansas with approximately 350 individuals attending. A series of speakers—colleagues and former students—discussed Professor Tuttle’s contribution to them and to the field of American history. It was a joyous event. Adding to the festivity was the fact that a lecture in Professor Tuttle’s honor was scheduled for the next evening, to be given by long-time friend and colleague, Leon F. Litwack. Dr. Litwack is a general editor of The Harvard Guide to African-American History and author of Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize. This was the first talk in what became an annual lecture series sponsored by the University of Kansas: The Bill Tuttle Distinguished Lecture in American Studies.

Interview

On a drive from Kansas City to Lawrence, a drive slowed to a crawl by a rainstorm, I asked the following questions of Professor Tuttle. This was not long after he retired:

What do you think is your particular gift as an historian? I think I can write well, say things clearly…bring a story to life.

I remember when you went to Stanford in the early ’80s. While there, you looked into the field of psychology for a school of thought that might augment your work. What did you find that proved helpful? When I was at Stanford, the psychologist Eleanor Maccoby told me that the field of psychology that I would find most helpful would be cognitive psychology. I was dubious at the time, but she was right. Beginning with Jean Piaget himself and moving to Lawrence Kohlberg and his student Carol Gilligan (author of In a Different Voice) as well as studies in political socialization, I did find this literature to be extremely helpful. I also found very valuable the writings on psychosocial stages by Erik Erikson as well as studies done in social learning theory in the 1930s–’40s, the work by John Dollard on class and caste, the work of Robert Sears, and others.

I always thought you were a very good father, but do you think that had you known about the work of the cognitive psychologists that you would have been a better father? In some respects, I do. Their work made me aware of how fragile the developmental process is, how easily it can be distorted and how important a father’s guidance and support can be. I knew this, of course, but their work drove it home.

At the end of your last book (Daddy’s Gone To War…), you suggest that the variables that most determine individual development and shape social change are age, culture, and history. Do you still see it that way? Yes, I do. That’s why I think historians and social scientists should work together. All three variables are at play in a person’s life. A given historical event affects each person differently depending on his or her culture and whether or not he/she is a child, an adolescent or an adult—to speak about it very generally.

And what about that crazy question we all ask from time to time: Do you think that some kind of individual consciousness continues after the “biological container” falls away? Yes, I do, but I don’t know how it works.

Find out who Sartre is

For years, the following was taped to Professor Tuttle’s refrigerator:

BEING AND NOTHINGNESS. When press dispatches from Paris reported in June 1964 that Jean Paul Sartre had joined the “Who Killed Kennedy Committee,” J. Edgar Hoover sprang into action. According to recently released FBI documents, the Director promptly scribbled a memo: “Find out who Sartre is.”

Professor Tuttle: “History, the brilliant James Baldwin has observed, ‘is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it with us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.’

“For this compelling reason, I believe it is incumbent not only upon historians, but also upon those committed to social justice, to, first, set the historical record straight when necessary and, second, to keep our historical heritage alive by remembering – and, when appropriate, celebrating – our freedom-fighting heroes of the past.”

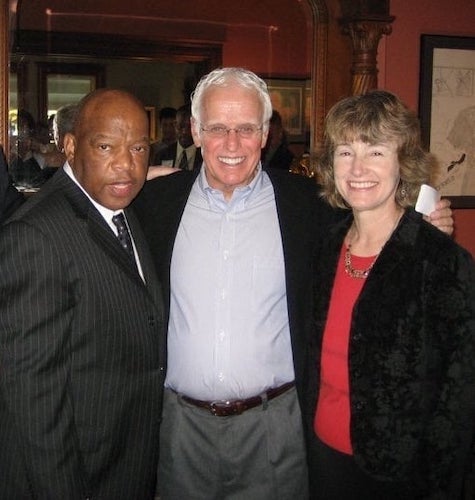

Professor Tuttle with his wife, Dr. Kathryn Nemeth Tuttle, hosting Congressman John Lewis in their home.

——————————-

Professor Tuttle is retired and lives with his wife, Dr. Kathryn Nemeth Tuttle. His mantra: Blessed and Contented.

He can be reached at tuttle@ku.edu.

David Thomas, PhD