THEATER ARTS: Douglas Paterson, Paul Boesing, D. Scott Glasser

For many years I have met regularly with individuals who have spent their lives teaching, directing, and participating in the theater arts. My friendship with these individuals has been integral to my ongoing education and I am deeply grateful to them.

“Man will get better,” said Anton Chekhov, “when you show him what he is like.” This must have been one of the reasons that theater was born, i.e., to show us what we are like. Theater strikes me as a nearly unbelievable invention. To create “a place for seeing”, as the Greeks defined theater (theatron), suggests how deeply felt is the human need to know and understand.

I continue to learn from the individuals profiled below and in what follows I hope to acknowledge in a small way their contributions to the theater arts.

————————–

Douglas Paterson — “we are all performers, performing ourselves”

Douglas Paterson grew up in Watertown, South Dakota. He went to Yankton College and later, Cornell University where he received his PhD in Theater. His career has focused on directing, acting, teaching, social justice, and facilitating theater-based experiences.

For more than three decades, Dr. Paterson has devoted himself to studying, applying, and adding to the Theatre of the Oppressed methods developed by Brazilian theatrical director and scholar Augusto Boal. In 1995, he launched the Pedagogy and Theatre of the Oppressed (PTO) Conference, an annual conference that continues to this day. In 2011, Dr. Paterson was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award in Leadership in Community-Based Theatre and Civic Engagement from the Association for Theatre in Higher Education (ATHE).

I first met Dr. Paterson in the early 1990s when we began a dialogue that over the years has been invaluable to me.

In 1977, Dr. Paterson left a tenure track position to act on his conviction that theater is activism of the most fundamental sort. Along with six others, he formed the Dakota Theater Caravan. For over five years in over eighty communities, the Caravan performed plays depicting the triumphs and struggles that characterize rural and small-town life in South Dakota.

In each town, members of the Caravan interviewed towns people: How did you get here? Why here? What has this community overcome? What should such a play about your community be about? From these interviews came plays entitled: “Dakota Roads”; Dusting off the ‘30s”; “Welcome Home”. After each performance, members of the Caravan visited with those in attendance, enriching their understanding of the region as they furthered their dialogue with individuals who had just witnessed the life of their community honored by a troupe of traveling artists. Overall, the Caravan was an exercise in the power of theater to build pride in community and place.

In 1990, Dr. Paterson reached out to Augusto Boal, Brazilian scholar, and author of Theater of the Oppressed and Games for Actors and Non-Actors. Boal used theater as a tool for empowering disadvantaged and powerless groups to act on their own behalf. It is work in line with at least two principles that fueled Dr. Paterson’s commitment to the Caravan: first, we are all performers, performing ourselves (everyday life is a stage) and second, theater can strengthen our capacity to act effectively for the benefit of ourselves and others.

There are now several theater companies and university theater departments throughout the United States using Boal’s methods. I once asked Augusto Boal who is most responsible for the growing interest in his work, especially in the United States. “Most responsible of all,” Boal answered, “is Dr. Paterson.”

How does this form of theater work?

In day-long workshops, scenes are created by participants, scenes that depict the problems and concerns currently faced by those participants in their families, neighborhoods, and communities. These scenes, when enacted, invite a rich and clarifying discussion concerning how best to address the problems depicted. However, the purpose of the enacted scenes is not simply to produce a clarifying discussion, but to have audience members enact their ideas for change within the scenes. Participants are invited to “stop” a given scene, take the place of one of the characters and then, complete the scene in keeping with their proposed solution. More discussion, more proposals enacted until the best of what participants can imagine is in front of them.

For Dr. Paterson, the theater that is most unforgettable and personally beneficial is the theater in which we choose to act, the theater that addresses our problems and concerns, and in which we (along with friends, colleagues, coworkers, and fellow citizens) work to find equitable and empowering next steps. Theater of this sort invites participants to overcome their hesitancy and to act on behalf of their own best interests. And, by so doing, give themselves a hard-to-forget experience, one that they will review and perhaps mull over, altering and enhancing their readiness to behave effectively when the issue of concern presents itself in everyday life.

I have found Dr. Paterson’s work both inspiring and illuminating, and I have used it to great effect. The Ethics of Human Development Training Program came alive with Dr. Paterson’s role-playing methods (along with Augusto Boal’s “exercises for non-actors” and Virginia Satir’s “sculpting process”). I thank him for that. I am one of many who have benefited from his important work.

————————–

One last point. Our friends are often telling us what we should read, listen to, plan on seeing, perhaps do. We should take note. Sometimes their recommendations benefit us greatly. It was Dr. Paterson who introduced me to the work of philosopher Bruce Wilshire… the following quote by Wilshire in line with one of the goals of Dr. Paterson’s work:

“One is not just a being in the world but (through theatre) becomes aware that one is a being in the world. One becomes aware of oneself as aware, interpreting, and free.” – Bruce Wilshire

Dr. Paterson can be reached at dpaterson@unomaha.edu.

————————–

Paul Boesing – “nothing to hold on to”

Paul Boesing is a composer, singer, actor, and voice coach. He has spent his life in the theater arts.

As an actor, Mr. Boesing was a company member of the Academy Theater in Atlanta, Joe Chaikin’s Open Theater Workshop in NYC, the Firehouse Theater in Minneapolis, and was, as well, an original member of Peter Brook’s International Workshop in Paris and London. In various theaters, he played the title role in King Lear, Polonius in Hamlet, James Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey into Night, Frank Hardy in Faith Healer, and George in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

What does a person gain or acquire by assuming these roles?

Mr. Boesing: “I learned that life is open-ended, always moving, nothing to hold on to. I know that sounds Buddhist, but you feel it when you’re on stage. Hold on too tightly and you miss your mark, you’re a step behind. In some respects, that was the point of the Open Theater movement. Each scene, though rehearsed, remains open to possibility. You are continuously composing what will be experienced by you, your fellow actors, and the audience.

“I was in Paris in ’68… Peter Brook’s International Workshop. We didn’t do much acting. The “theater” in the streets captured our attention. While the ’68 uprising was about many things, for me it was about freedom of expression, liberation from what keeps us from creating as freely as we would like.

“Of course, if I were to look inward there are other reasons I was drawn to acting. On the Enneagram I am a nine. Buddha also was a nine, or so I am told. A nine operates from feeling, comes at others “feeling first”. When I was in the sixth grade, I had a part in the school play. I had to pound the table. Express anger. There was applause and I liked that, but I remember feeling a release. That’s what I’ve learned over the years: The very best parts empty you, and when done, you feel a sense of completion. Stillness. That’s what acting teaches you… the deep satisfaction that comes from playing your part fully and well.”

As a composer, Mr. Boesing created a concert of songs (with dance) set to the poetry of W.H. Auden. Called Tell Me the Truth About Love, this work premiered at DanceSpace in New York City with Tom Bogdan, tenor, a member of the Meredith Monk Ensemble. For the Nebraska Shakespeare Festival he wrote the songs and incidental music for As You Like It, and scores for Othello, Antony & Cleopatra and The Tempest; and then, a different set of songs for As You Like It for the University of Kansas, which won a Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival Award.

Mr. Boesing’s music-drama, The Mothers of Ludlow, with a script and lyrics by Martha Boesing, premiered at Youth Musical Theatre Company in Berkeley; and was performed by The Bluegrass Opera of Lexington, KY, commemorating the Opera’s 100th anniversary. Mr. Boesing won an international art song competition with his setting of W.B. Yeats poems entitled Like an Old Song.

“In truth,” commented Mr. Boesing, “composing has been my life, even more than acting. I love acting because it’s collaborative. Composing is solitary. It’s an opportunity to create something that is entirely your own.

“I often find my inspiration in poetry. Yeats, Auden, Rilke, Shakespeare. I try to create in my composition the same feeling that is created by the poet. Yeats once said something like ‘the image brought in to enhance and expand the poem is itself enhanced and expanded in return.’ When I’m successful, my composition meets the poem on equal footing, each is enlarged by the other.”

A good example of this last point is Mr. Boesing’s musical interpretation of Photograph, the three-page five-act mini-play by Gertrude Stein. First produced in 1987 by the Actors Theater of St. Paul and the Red Eye Theater of Minneapolis and co-sponsored by The Walker Art Center and Nautilus Music-Theater, it was, in one reviewer’s opinion, an “inventive, probing attempt to flesh out in music what Stein was trying to say in words.”

That same reviewer (Tad Simons) went on to write: “If a genius (referring to Gertrude Stein) would have the guts to write a five-act three-page play, it takes something close to genius (referring to Mr. Boesing) to stretch it into an hour of captivating musical theater.” Mr. Boesing’s “musical compositions range from dirges and arias to Latin percussion riffs, gospel, and be-bop…” As to Mr. Boesing’s method, “(He) uses the same words over and over but attaches them to intentionally incongruous associations — a very poetic and succinct way of capturing Stein’s ideas about the frustrating but often delightful capriciousness of the artistic imagination.”

After listening to a recording of Photograph, I found myself in agreement with the reviewer. Mr. Boesing’s musical interpretation of Photograph adds to what must be a central theme of Stein’s play: life floats on… you can’t quite grasp it or hold it still long enough to know what it means… and yet, Mr. Boesing’s composition suggests, one moment leads to the next often in the most surprising and pleasing way.

————————–

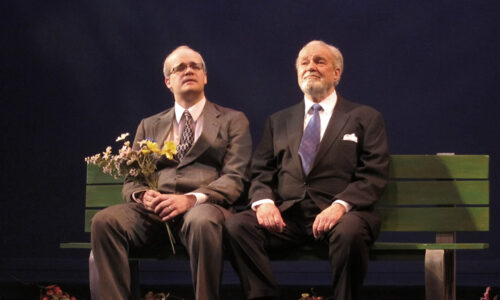

Mr. Boesing’s ninetieth birthday was celebrated with several performances of “Who’s Afraid of Gertrude Stein?”.

For more on “Who’s Afraid…” or to contact Mr. Boesing: paulboesing@gmail.com

————————–

D. Scott Glasser – “With this, we can civilize the world”

“…theatre reveals life… it is life-like. …and life is theatre-like.” — Bruce Wilshire

Scott Glasser has devoted his professional life to the theater arts, as have the gentlemen profiled above. He has directed over 180 productions and has acted in 120 others. Along with Dr. Paterson, he was a founding member of the Dakota Theatre Caravan. He helped create a flourishing theater program at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon, was a professional director/actor in the Twin Cities for 13 years, was the artistic director of the Madison Repertory Theatre in Madison, WI, and was associate artistic director of Nebraska Shakespeare. Since 2004, he has been Professor of Theatre at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

His directorial credits include: Marat/Sade, Man of La Mancha, his adaptations of Much Ado About Nothing and Aristophanes The Birds, Titus Andronicus, The Cripple of Inishmaan, Our Town, Dracula, The Secret Garden, Shaw’s Misalliance, The Importance of Being Earnest, A Streetcar Named Desire, Dancing At Lughnasa, Six Degrees of Separation, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Three Tall Women, Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, The Man Who Came To Dinner, The Winter’s Tale, Julius Caesar, Hamlet, The Tempest, Richard III, Othello, Antony and Cleopatra, Love’s Labour’s Lost, King Lear, and Macbeth.

As an actor, he has performed as The Mayor in Jeffrey Hatcher’s adaptation of Gogol’s The Government Inspector, Gaston in Picasso at the Lapine Agile, Phil Hogan in Moon for the Misbegotten, Henry in The Real Thing, Trigorin in The Seagull, Henry Higgins in both Pygmalion and My Fair Lady, Felix in The Odd Couple, Captain Hook in Peter Pan, and Shakespeare’s Mercutio, Shylock, Touchstone, Benedick, Dromio, Edgar, Adam, and Hamlet.

This serves to document Mr. Glasser’s career. More specifics could be added. However, for purposes of this exhibit, other questions and concerns present themselves.

We are made by what we do. Different professions (and lifestyles) lead to the buildup of different muscle systems, different skill sets, different psychologies. What does a life in the arts, in theater, have the potential to make of us?

And further, what are we seeing as we sit quietly in the audience, safely distanced from the drama that unfolds before us? Why are we interested?

To the first question, Mr. Glasser responds: “A life in the theater increases one’s ability to enjoy life… to look into life, to recognize the tragedy and the comedy, to feel pity, wonder, fear, but at base, to be deepened as a person; and so, to appreciate and enjoy the fact that one is alive.”

“The performing arts,” Mr. Glasser writes, “tests one’s limits. They encourage exploration of the unknown, they challenge the intellect, combine skill and instinct, require collaboration, celebrate both the individual and teamwork.” And, he adds, “they demand punctuality and discipline.”

As for the second question: What are we seeing as we sit in the audience, observing actors in costumes, masked, enacting foolishness, folly, the heroic and the despicable… what do we see?

“We see a mirror,” Mr. Glasser has suggested, “a mirror that permits us to see past our own masking and so, to identify with the characters before us, allowing that their actions under similar circumstances could be our own.”

“Without an audience, the performing arts are half-complete,” continues Mr. Glasser. “It is their communal sharing of our common humanity that puts live performance in a unique place within our society. It creates a social consciousness that transcends preconceived borders.”

In other words, live performance has the potential to enlarge our circle of concern. It increases the number of individuals, seemingly different from ourselves, with whom we can identify.

When theater was invented—I don’t know enough to say when, where or by whom—the inventors must have wanted to spread it far and wide. Both mirror and metaphor, a way of seeing ourselves and a way of seeing the world; the inventors must have thought: With this, we can civilize the world.

————————–

In the Spring of 2024, Mr. Glasser retired from his position at the University of Nebraska/Omaha. I’m delighted to say that for his first post-retirement job, he directed the stage reading of Timetable, a play with music about the healing effects of wonder and awe.

Mr. Glasser can be reached at sglasser@unomaha.edu.